The Real Ted Lasso Lives in North Carolina

In 1971, Vaughn Christian was invited to coach the Appalachian State soccer team, even though he had never played the game. He won five conference titles in seven years.

Vaughn Christian never liked attention. But on this night, surrounded by about 60 people, everyone focused on him.

He tried to deal with it as best he could. He’d shake his head, deflecting the credit he’d just received for his impact on another person’s life. He’d look down at the floor, fighting away tears and finding just enough composure to keep listening. Or he’d smile, lighting his eyes and bunching up the wrinkle lines from a teaching career full of joy. He might even laugh, too, if a memory tickled him.

Christian used all these, sometimes in sequence, as his defense system against that attention. But none of them really worked.

Walk through the double doors of the chancellor’s suite at Appalachian State University’s Kidd Brewer Stadium, and you see the far wall is a massive stretch of glass. Christian and his wife of fifty-six years, Beverly, sat at the center of this room. The space, on the sixth floor of the athletics tower, overlooks the middle of the football field that becomes the epicenter of Boone, North Carolina, every fall. Howard’s Knob, a mountain that towers a thousand feet above Boone, sits high in the left of the sightline, with the west side of campus tucked in front.

But the only reason to take in the view on this March night was to scan toward the right end zone, where the scoreboard lit the darkness. “HAPPY BIRTHDAY DR. VAUGHN CHRISTIAN,” the sign read, with a signature line below. “—YOUR FORMER PLAYERS.”

Christian taught in the physical education department at App State from 1971 to 2003, rising to department chair. He was a few hours away from his eightieth birthday, and this surprise party featured former students from all over the country, some he hadn’t seen in decades. Now in their 60s and 70s, they returned to their alma mater for one reason: their old soccer coach.

These men personified a unique period of Christian’s life, when he coached a sport he never played. For seven years, Christian led the Appalachian State men’s soccer team. And during that time, he authored what’s likely the most drastic rise of a program in the school’s athletic history. From 1971 to 1977, he won championships and piloted high-flying offenses. He made the school a meteoric figure in the South with an international mixture of players who brought thousands of fans to watch their games.

“Any time anybody came to me and said, ‘Professor, thank you so much for your contribution to my life,’ immediately, I went to you. Because you started everything.”

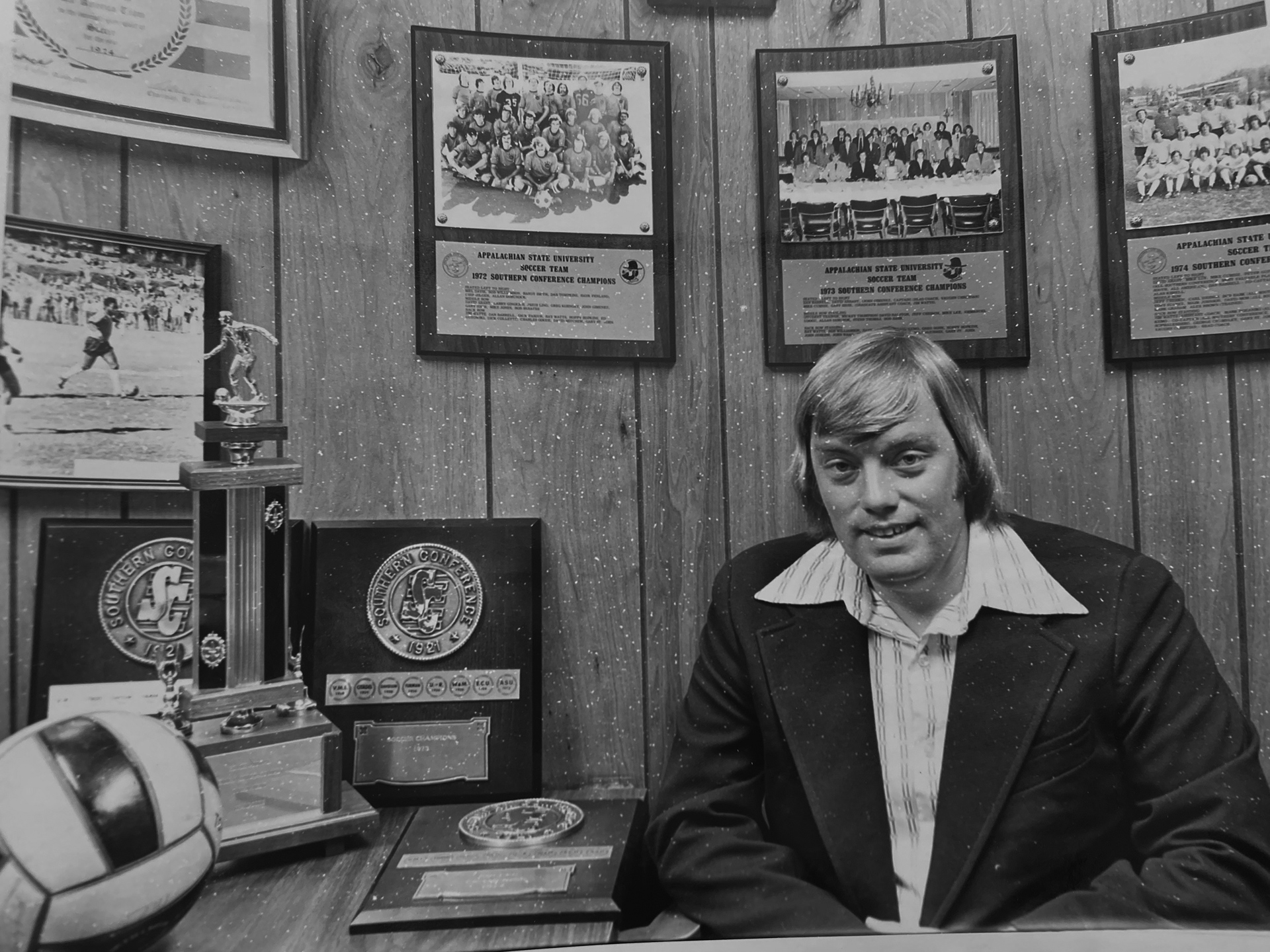

The chancellor’s suite was decorated with mementos from his tenure, a time capsule exploded into every corner. Soccer balls from title-winning seasons, bearing the patina of victories past, sat close to the entryway. Newspaper clippings, all yellowed, scattered the bar tops. Plaques with team photos—the uniforms and hairstyles as snapshots of the era—lined the right wall.

There was a cake in the school’s black-and-gold color scheme. There were drinks. There were a few gifts for Christian. But his players’ presence meant the most, even if Christian had to keep it together through the speeches that tore him up.

Christian heard sentiment after sentiment, from first impressions to coaching platitudes to the sheer effect he made on the paths of their lives. He witnessed proof of his life’s work.

Billy Viger, 73 and a member of Christian’s first App State team, choked up about the man that “made me the coach I am, and the teacher.”

Shake head. Look down. Smile. Hug.

Fernando Ojeda, 68, a Miami native who spent his childhood in Costa Rica, became a college professor. He thinks of Christian often. “Any time anybody came to me and said, ‘Professor, thank you so much for your contribution to my life,’ immediately, I went to you. Because you started everything.”

Shake head. Look down. Smile. Hug.

David Mor, the man who organized the surprise party, came from Israel to play for Christian. Now 72 years old, he replicated much of Christian’s professional blueprint.

“I played for the Israeli national team,” Mor said with a trembling voice. “I’d never seen someone with his attitude, his leadership. To show you how he really impacted my life…I ended up teaching for 28 years in college and coaching varsity soccer.” After Mor got the last word out of his mouth, he lunged for a hug from Christian.

Shake head. Look down. Smile. Big hug.

All the speeches ended nearly the same way: with a thank you, a happy birthday wish, or simply an embrace.

To be truthful, Christian wasn’t completely surprised by the party. Beverly had told him a few days earlier to limit the shock. But he would be overwhelmed anyway by the turnout of approximately 40 players and App State coaches he worked alongside. Before the speeches, one gift provided a warning for how emotional Christian’s next couple hours would be. It was a glass trophy, a cube tilted on one of its corners. An engraved plate on the base caught his eye. He scanned it as people clapped, letting out a “wow.”

“A good coach can change a game. A great coach can change a life.”

“Going to be tough to get through,” Christian said, loud enough for all to hear. It sure would. After holding the trophy up for everyone to see, he was prompted to read it aloud.

“A good coach can change a game. A great coach can change a life.” He let out a “whew” as applause started again.

The phrase highlighted why he’d be so uncomfortable throughout the night, and why he wanted to be a teacher in the first place.

His work was never about him. It was always about helping his students grow.

Maybe you’re already thinking it. Vaughn Christian is the real Ted Lasso.

The mustachioed gaffer of fictitious AFC Richmond on the Apple TV+ series of the same name, Lasso uses his folksy charm, an unflappable focus on kindness and his love of coaching to navigate the most beloved sport in England (and the rest of the world).

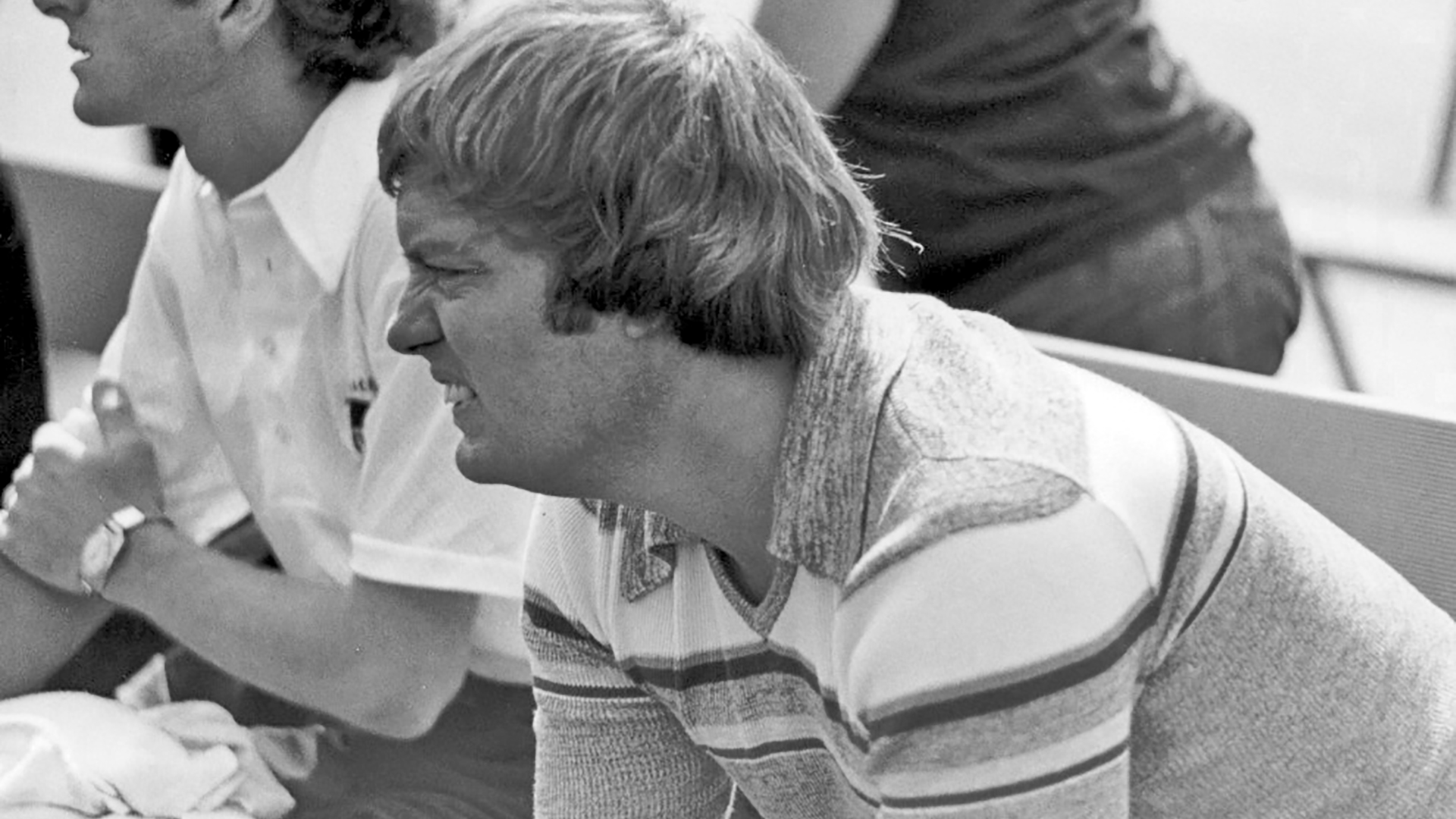

But Christian didn’t go to Europe and learn the game at the top level. He didn’t face the intense scrutiny and job insecurity that comes with professional or college coaching today. And, judging from some photos from his coaching tenure, it appears he never had a mustache—although at one point there were some thick, perhaps disco-inspired sideburns.

What he did, much like Lasso, transcended all that. He used soccer to reach people. That flourished during his time at App State, but it started when soccer first entered his life in the mid-1960s.

Christian was born and raised in Bristol, Tennessee. He played baseball and ran track. He knew early on that he wanted to teach. He entered Peabody College, which is now part of Vanderbilt University, in 1961. As an undergrad, the physical education and athletic departments approached him about coaching a soccer club sports team. He’d never even kicked a ball. Why him?

“I think they felt I had the leadership qualities to try to make something happen,” Christian says. “At least I hope that's what it was.”

“He loved it and was wanting to pass along the love of that game, which was still fairly new to him, to the guys that were interested.”

Christian thought he had a knack for the important aspects of a team game: the psychological navigation of successes and failures, the on- and off-field communication skills, the drilling and conditioning. But he needed a tactical crash course from someone who understood the layered nuances of soccer.

Fortunately, the Peabody student base featured a large international population, many with extensive knowledge of the game. Christian, very luckily, met Mohammed Sabie (pronounced SAH-bee). Much of Christian’s foundation in the sport can be traced back to a small metal board in Sabie’s old office. The board showed a miniature soccer field. Sabie would work the pieces around, the clacks and drags of magnets showing Christian different formations and movement. At first, he saw Sabie as intimidating and imposing. Tall with coal-black hair, he looked every bit of the former athlete he was. Turns out, the opposite was true. Christian discovered Sabie was inviting, especially to someone looking to learn. Sabie, at the time, was about 10 years older than Christian. An immigrant from Baghdad, Iraq, he was at Peabody getting his doctorate. His daughter, Mona Sabie Womack, says he came to the U.S. through an Iraqi government program to help students gain international experience in the hopes they would return and teach in their home country. In Iraq, her family members told her, her father had been a basketball and track star.

“He really wasn’t a high-achieving student academically in Baghdad,” Womack says of her father. “But he was very driven. And so, when he came to the U.S., him getting his education was what he believed was the sole key to his success in this country.”

Sabie ultimately stayed in the U.S. and became a significant soccer figure in Kentucky. He taught at Morehead State University for 38 years, coaching at the school for 28 of those.

Those early moments with Sabie became the pillars of Christian’s confidence as he continued his soccer education.

“He was kind and patient,” Christian says. “(I was) overwhelmed with his knowledge, even more in that he would want to share so much information with a young person who was infringing on his time.”

Christian kept fueling his soccer interest after those days with Sabie. He would finish his undergraduate at Peabody in 1965, and get his masters from there the following year. He got his first teaching-and-coaching opportunity at Oxford College in Georgia, a liberal arts school, which, although located 45 minutes southeast of the city, is part of Atlanta’s Emory University.

Being so close to Atlanta, Christian would drive to watch practices for the Atlanta Chiefs, the city’s first pro soccer team in the long-since defunct North American Soccer League. He would film practices and techniques of players, eventually bringing some of his Oxford players with him for those learning sessions. He worked at Oxford for a year, returning to Peabody for his educational specialist degree, then spent three years getting his doctorate at Louisiana State University.

In the thick of all this, Christian met his future wife, Beverly, at Peabody. She was surprised by his growing interest in a sport that had little traction in their home state of Tennessee. But she recognized it as another way for him to teach.

“He loved it and was wanting to pass along the love of that game, which was still fairly new to him, to the guys that were interested,” Beverly says.

They were married in 1967, the same year a friendship started between the two and Jan Watson. Watson, a fellow longtime faculty member, became Christian’s connection to Appalachian State in 1971, when Watson found a note in her mailbox: “Needed: Soccer coach who can also teach exercise science.”

Christian had the job soon after. During one of the numerous back-and-forth trips to their new home, he and Beverly stopped for gas around Roan Mountain, not too far from the North Carolina border. They were greeted by a store attendant with a thick mountain accent who made the “regular” in regular gas a two-syllable word. Because they were still looking for a house, their agent had sent the local newspaper so they could peruse the classified ads. On the front page, photos from a moonshine raid sat above the fold.

“Oh, man, where are we moving?” Christian remembers his wife saying, nervous about their future in Boone.

They’ve called that place home for the last 52 years.

Vaughn Christian’s first outing as a soccer coach was cruel. The demoralization sat heavy on his players in the locker room afterward, the air thick with embarrassment. Christian’s Appalachian State Mountaineers got an absolute walloping to open the 1971 season, courtesy of the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. App State lost, 9-0.

The team’s skill level wasn’t even close to the Tar Heels’. Christian’s poor goalie, Charlie Sykes, got beaten into the ground. He was bleeding, Christian recalls, from throwing his body toward so many shots.

“They must have taken 50 shots on goal,” Christian says. For reference, the most recent national championship game between Syracuse and Indiana featured 35 total shots, with only 13 being on goal. Exaggerated or not, the Tar Heels launched missiles at Sykes the whole game.

There was one thing that Christian couldn’t understand. Why would the UNC coach, Marvin Allen, let his team pummel another that was clearly overmatched?

“They’ve got to practice tomorrow afternoon,” Christian said to Allen after the game. “What am I going to tell them?” Tell them we beat you, he remembers Allen saying, snidely.

So before he walked away from Allen, he issued a warning. App State will get you one day. Christian told his team the same shortly after: “This will come back to haunt them at some point. You guys may not be here (for that), but your memories will be with me when we beat them,” Christian promised.

Billy Viger was a senior on that team. He remembers a different part of Christian’s message to that sullen group. Christian was surprised by their play and struggles, Viger heard him say out loud. He knew the players were, too. He also reminded them they could be better. They were going to improve.

“He was a guy that, in my opinion, they could’ve told him he was going to be a volleyball coach, and within a year, he would’ve been a hell of a volleyball coach.”

“Those are the things that he was excellent at, you know? Keeping us together as a team,” Viger says.

Viger had met Christian a little over a month earlier. The coach occupied an incredibly small office in Broome-Kirk Gymnasium. The tiny space was orderly, Viger remembers, and Christian looked the part of a well-dressed professor. He also communicated differently than any other coach Viger had played under. Christian was Viger’s third coach in four years. On top of that, Christian didn’t get to meet his team until early August. They had to learn from one another on the fly.

But that 1971 team did get better. They went 6-6, playing a schedule featuring competitions with a few Southern Conference schools. They became full-time members in 1972 and shocked the conference with an 11-4 record and a championship in the Mountaineers first full year of eligibility. They made up for their lack of talent and depth by pummeling opponents with 90 minutes of grit.

“Back then, we out-hustled people,” says Charles Goode, who played in the early days under Christian.

Christian built a summer habit after that first season. An envelope arrived at players’ homes. Jack Pasour remembers getting one at his Denver, North Carolina, address.

“What in the world is that?” he remembers asking himself as he noticed Christian’s name as the sender. Inside was a workout and a set of tables that listed prescribed distances and targeted times. The team had to follow Christian’s workout schedule and hit the milestones to approach game shape. They also had to mail in their progress for Christian to monitor.

While Christian coached, he was also responsible for three or four classes a semester. Some of his former class load explains why he drilled fitness as his main building block: physiology, anatomy, kinesiology, measurement. and evaluations (a stats course).

Mike Schaeffer, a former assistant under Christian, calls Christian’s fitness training the most efficient he’d ever seen. Athletes today wear equipment that provides real-time data on their movement, energy and vitals. That didn’t exist in the ’70s. Christian would get players to check pulse rates immediately after a sprint, then change the time targets.

“He was a guy that, in my opinion, they could’ve told him he was going to be a volleyball coach, and within a year, he would’ve been a hell of a volleyball coach,” Schaeffer says. The coach’s grueling conditioning helped propel the program much faster than Christian expected.

A scene from that first championship run seared itself in Christian’s mind. It came against Davidson College after the regular season, a match to determine who would go on to play William & Mary in the SoCon championship. Davidson had beaten the Mountaineers in the regular season, but they wouldn’t repeat. The two slugged through regulation and into extra time. Referees, Christian recalls, eventually told the teams that the first to score would be the winner. Magic happened for Appalachian when Randy Smith centered a ball over to Chip Hilger, who passed it right to Pasour for the game-winning goal. The team exploded as the final whistle secured the 1-0 victory, and Christian joined him.

He’d never seen such enthusiasm from his team, the piled-up losses in the past finally overcome. Christian didn’t have many scholarships to offer players, or even much of a budget. Yet his players won in spite of that.

“That was probably my greatest thrill,” Christian says. “Because I was under stress, I felt, for a whole year because people were doubting what we were going to do or whether we could do it or not.”

App State beat William & Mary the next week by the same 1-0 margin, securing Christian’s first championship. Then he used that early success to start building rosters that could replicate it. Christian didn’t recruit for his first two seasons. His 1971 and 1972 teams were mixtures of the guys who stayed after the coaching change and guys who showed up at tryouts.

The next season became the harbinger of a higher skill level that would last throughout the coach’s run with the program. Christian points to the additions of Frank Kemo (U.S.) and Emmanuel “Ike” Udogu (Nigeria), both strikers, ahead of that season.

He scooped up Kemo out of New Jersey thanks to a bond created with the player’s dad. Christian found Udogu through the recommendation of a fellow faculty member, who’d seen him playing about an hour away at Montreat College.

Kemo and Udogu became dual spearheads of a juggernaut offense. The Mountaineers won the SoCon title again in 1973. Christian had found his first difference-making players.

Guys like that made recruiting much easier going forward.

“There was a domino effect,” Christian says.

The soccer goals at Appalachian State humbled the Mountaineer players, no matter their seniority or talent level. These were not the lightweight goals of today. These goals were steel and brutally heavy. And when time came to move them, every player helped lug these goals back and forth, from under the bleachers to the field.

“It was a pain in the ass,” laughs Alan Kissell, a backup goalie with the team from 1974 to 1977.

But the players had to move them before and after every practice. Every home game? Yep, even then.

Those goals never changed during Vaughn Christian’s coaching stint at App State. But the teams sure did. After those first two conference championships, the roster got talented in a hurry, and developed a real depth of international flavor. In 1974, he welcomed in David Mor, a goal-scoring midfielder from Israel. App State won the conference title again, and Ike Udogu earned SoCon player of the year honors.

Christian’s caring spirit gave him more recruiting luck ahead of the 1975 season. He secured three players from Miami Dade North after seeing them lose in the junior-college national championship game held in Baltimore, Maryland. Christian’s primary target on that team was Fernando Ojeda. And Christian’s low-key, earnest approach made the Costa Rican player ultimately decide to come to App State.

Ojeda remembers being crumpled on that field in Baltimore, looking down at the pitch and letting the loss sink in. He heard Christian say, “Now is not a good time to talk, I can tell. Take this information and read it. I’ll be calling you a little later on.” It was sincere, genuine and polite, Ojeda thought. After a scholarship negotiation, Christian asked Ojeda to convince two other teammates—Luis Sastoque and Ronnie Groce—to attend App State, too.

Not only had recruiting steam picked up, but eyes around the nation started noticing Appalachian State. Their scores and victories stood out in the weekly NCAA newsletter. Then, the only way to make the NCAA Tournament was to be a top-four team in the regional rankings, voted on by coaches. More wins helped attract more votes.

“I could make a difference by going to the classroom (full time). I felt I had a better chance of changing more people by getting them in the classroom and me teaching. I wanted them (his students) to change the lives of young people.”

The Mountaineers won another SoCon title in 1975, and it was Mor this time who earned the player of the year award. That season featured a twelve-game winning streak for an undefeated regular season that started with an opening victory against UNC, fulfilling on Christian’s promise to beat the Tar Heels and their coach Marvin Allen. The real prize came when Appalachian State earned a spot in the NCAA Tournament. App State had never reached that level in any sport. They drew reigning national champion Howard University and saw their season end in a 3-1 defeat—their only loss of the season.

The players mentioned so far are a small cross section of the team’s skill and international diversity. Christian coached others from Colombia, England, Greece, Guyana, and Kenya.

The biggest star, though, arrived in 1977, Christian’s last season with the program. Thompson Usiyan. He was already a known commodity at the international level. Usiyan was set to star for the Nigerian Olympic team in 1976. But Nigeria was one of many African countries to participate in a boycott of the games to protest the apartheid regime in South Africa.

Usiyan decided to go to college after that, selecting App State because so many of his countrymen, like Udogu, had success there. Usiyan's explosive play and on-field grace led to what is still is the top goal-scoring career in NCAA history. In forty-nine career games, Usiyan scored one hundred and nine times. He won three Southern Conference player of the year awards. Missing most of his junior year (1979) with an injury may be the only reason he didn’t win four. (Side note: Kingsley Esabeman, his App State teammate and fellow Nigerian, won it that year.)

Alex Brown, 67, was the team’s athletics trainer from 1974 to 1979, who went on to a long career in college athletics. He spent 32 years as the athletic trainer for University of Oklahoma basketball, working with future NBA stars like former No. 1 overall pick Blake Griffin, Buddy Hield, and Trae Young. Brown says that Usiyan was as good of an athlete as all of them.

“His playing style? He could play whatever style,” Brown says. “He had God-given talent.” Usiyan powered the Mountaineers to another SoCon title in 1977 in a 22-goal campaign for the freshman. They appeared again in the NCAA tourney, losing to Clemson in the first round, 3-1.

“I'm so excited, you have no idea. It means so much to me because I heard it from almost everyone, how influential Coach was on their lives.”

Usiyan’s arrival came in a season Christian saw as a natural exit point. The coach had his first child the year before. Beverly watched his already hectic schedule, split between the field and the classroom, get even harder for him. He never planned to be a career coach, anyway. Christian’s goal was to help the program improve, then hand it off to someone who could keep it trending in a positive direction.

Christian began looking for his replacement and caught the eye of Hank Steinbrecher, the coach at nearby Warren Wilson College. Steinbrecher wound up building a brilliant career in soccer, becoming the secretary general of the United States Soccer Federation from 1990 to 2000. He won the SoCon title in all three of his App State seasons, making two NCAA Tournament appearances from 1978 to 1980.

“I inherited what potentially was the best college soccer team at the time,” Steinbrecher said in a call played aloud at Christian’s party. “And Vaughn put that team together.”

Kissell, a senior during Christian’s last year, spent many hours in Christian’s office outside of practice. During one of those meetings, after the 1977 season, Christian told Kissell he planned to leave the coaching profession.

“He was stepping down, and he was going to be focusing more on building the performance lab and kines (kinesiology), and so it was kind of like ‘OK, that makes sense,’” Kissell, now 66, recalls. “And that’s what he did.”

All told, Christian won five SoCon soccer titles in seven seasons and then, with no fanfare, slipped out of view. He focused on his teaching for the next 32 years.

“I could make a difference by going to the classroom (full-time),” Christian says. “I felt I had a better chance of changing more people by getting them in the classroom and me teaching. I wanted them (his students) to change the lives of young people.”

On the morning of Vaughn Christian’s surprise party, David Mor, the Israel player who came to App State for the coach’s first season, stood with a cup of coffee from his hotel room. A rental-car snafu at the Charlotte airport resulted in a delayed arrival. He sipped and waited for his plan to start in motion.

“I'm so excited, you have no idea,” Mor had told me a couple days earlier. “It means so much to me because I heard it from almost everyone, how influential Coach was on their lives.”

The day began with a tour. A pair of current students led a group of about 20 former players, staffers and loved ones around campus. The players took over the guides’ work. This was our library, they told the guides, pointing to a building now used for classes. When the group arrived at Varsity Gym, home to many athletics teams during its life, they listed off music events that passed through the small venue: Bruce Springsteen, Billy Joel, the Beach Boys. The student guides couldn’t believe it.

After lunch, some former players put on gear and played a few scrimmages in the football program’s indoor facility. Mor and Ojeda can still get their feet on a ball. Others battled years of rust. But today, a half-century later, it didn’t really matter how anyone played.

Christian walked into the indoor facility halfway through the games, and the whole place erupted. His former players stayed in Christian’s orbit the rest of the day. Following a team dinner, Christian sat through the hour-plus of stories about him.

When it was his turn to talk, he recounted memories that stood out most. The walloping by and ultimate defeat of UNC. The victory against Davidson in 1972 that set up the team’s first championship. The rowdy crowds. The limited budgets. The beautiful game.

“He always saw what’s inside of that person, and he always tried to guide you in the right direction.”

Christian’s speech had stories and sub-stories. Threads led to others. He tried to keep it chronological, but he hopped around the timeline a bit, too. It bothered no one in the crowd, all fixed on the old soccer coach.

The earlier testaments had really rocked Christian. There was also some unavoidable, underlying sadness to the party. A hard part of aging is the people lost along the way. At the start of the gathering, names of deceased former teammates were shared in a moment of remembrance. The list numbered in the double digits.

Sabie, Christian’s early mentor, died in 2007. He and Christian hadn’t talked since their Peabody days. Usiyan, the star of stars in that era of App State soccer history, died two years ago. Jim Jones, the athletics director who hired Christian and supported the program even when funding was thin, died a few days after the party.

And they all mourned a common loss. Appalachian State discontinued the men’s soccer program in 2020 due to financial hardship from the COVID-19 pandemic. That wound hasn’t healed yet. Christian still wrestles with that pain.

“I hated that you guys put in so much time when we asked you to, and you did it and worked your tails off, and we won the games,” Christian said. “Those memories can’t be taken away, but it hurt for me, and really hurt for you guys, when they dropped the program.

“That really hurt me. But we got the memories, and we’ll keep coming back and eventually, maybe, it’s going to happen. Maybe not in my lifetime, hopefully in your lifetime, it’ll come back.”

There was laughter too, tons of it, carrying out the open windows and over the football field. The stadium had changed, and so had the field turf. But when the memories floated across the playing surface, they danced over the ground the players’ cleats had dug into nearly a half century ago.

Christian couldn’t sleep the night after the gathering. His head swam. Swirling reflection kept him awake. Fun stories, like the one from Luis Sastoque about the long walks from the locker room, near the center of campus, up Stadium Drive to the field. He loved how good they all looked in their uniforms before games, enjoying the chance to strut in front of other students. Kind thoughts like Jan Watson’s. The day before she retired, someone asked, “What was the best thing you did for Appalachian?” Watson only needed a second. Vaughn and Beverly Christian were her answer. Validation of life-altering change he brought into people’s lives, like what Michael Shepherd shared. A starting goalkeeper from Guyana affectionately known as “Sheep,” said he doubted he would be in this country without Christian. He felt Christian’s great gift was the connection he developed with his players, no matter where they were from.

“He always saw what’s inside of that person, and he always tried to guide you in the right direction,” Shepherd, 70, said.

A little over two weeks later, Christian had just returned home from Jones’ funeral. Even with the somber events of that day, talking about his players lifted his heavy spirit. Christian had made them better, and they had taken his lessons throughout the course of their lives.

The only regret of his surprise party? He didn’t get to tell a story about each player, to acknowledge the effort they made for him.

“I wanted to say something personally about whoever was there,” Christian says. “And I would’ve had a story for any of them, but good God. it would’ve lasted way too long.”

Even in his moment, it was about his students. It wasn’t about Vaughn Christian.

It never has been.

About the author

Ethan Joyce is a writer based in North Carolina. He works as a tech reporter for the Sports Business Journal, and he authors the Chasing Joy newsletter.