Making Sense of Mississippi

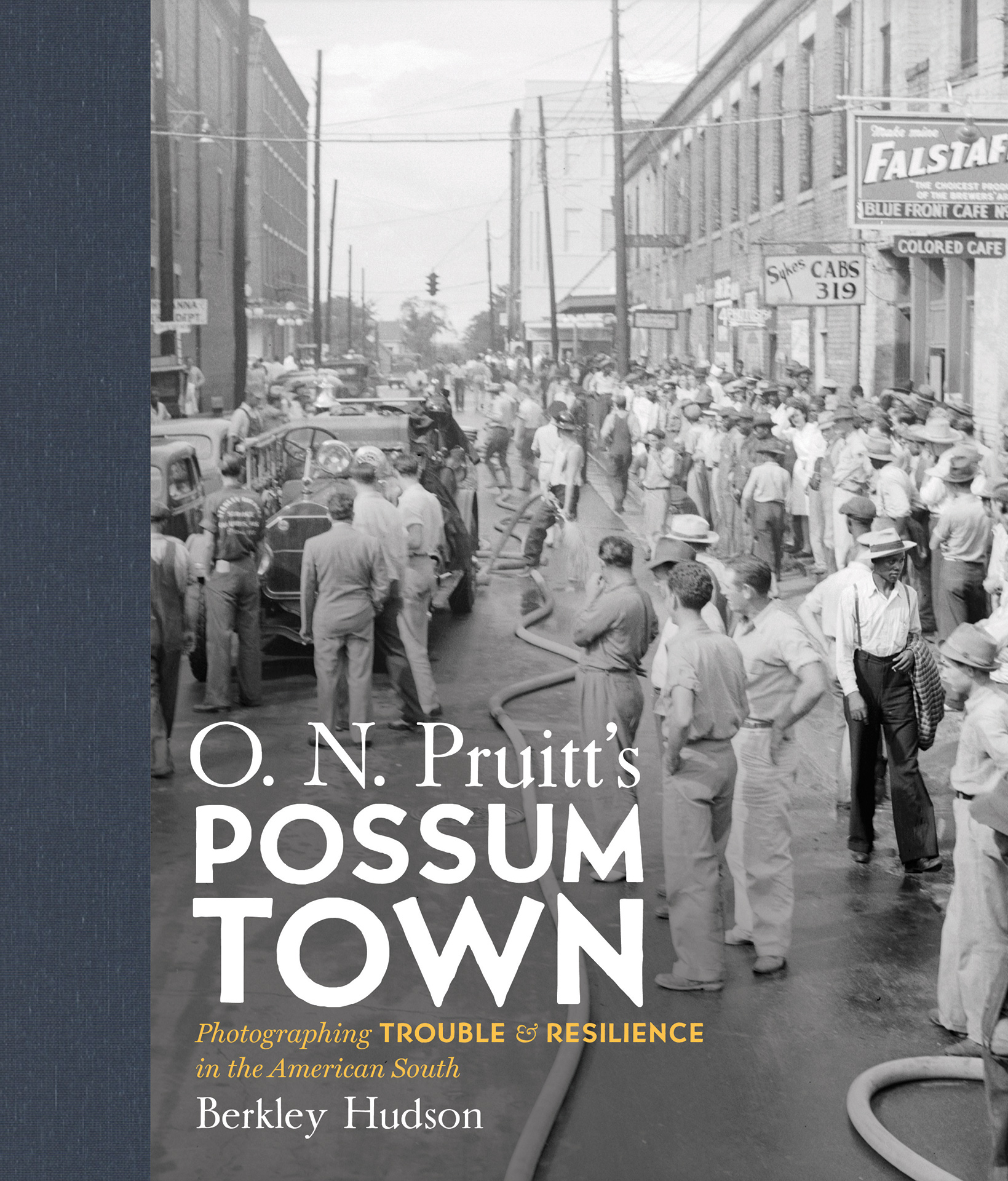

O.N. Pruitt was the “picture man” where journalist Berkley Hudson grew up. Pruitt’s photographs helped Hudson understand the state he ran away from — and the state that drew him back.

The Fog Machine passes me on the street, this humid Mississippi day in June 1994. I smell the insecticide that wants to find mosquitoes and kill them dead. So, I scurry out of harm’s way to avoid breathing poison.

When I was a boy in the 1950s, plumes of white smoke would spew from the back of the fog truck. On our bikes, we’d chase that truck like crazy. We didn’t know better. We’d go in and out of the bitter, intoxicating smell that wafted along streets of antebellum homes mere blocks from unpainted wooden houses with outhouses in the back, in our town, Columbus, in Lowndes County, between the Tombigbee and Luxapalila rivers along Alabama’s border in northeast Mississippi.

This June 1994 evening, my mother at supper says she’d just watched the television weatherman. “Two inches of rain today. Boy, I’m grateful for it.” Yep, I say.

I’ve come from Los Angeles where I’ve been working as a writer on the Los Angeles Times. For a personal project, I’ve returned to unearth lost stories, some uplifting, some horrifying, buried in a batch of thousands of photographs made by Otis Noel Pruitt.

For our part of northeast Mississippi, where my Anglo-European ancestors arrived in the 1830s, Mr. Pruitt was the “picture man,” from 1920 to 1960. I and four white boyhood friends in 1987 rescued his negatives and prints from history’s dumpster. A white conservative photographer who remarkably documented Black and white community life, Pruitt had photographed each of us as boys, myself mainly at family gatherings at my grandmother’s rambling Victorian house filled with antiques and Pekinese.

After four days back home, I hear somebody say the N-word. It happened after Sunday services at the First Baptist Church when the associate pastor had preached, “What’s Love Got to Do With It?” On the steps, we were talking with a former sheriff I’d known my whole life. He’d been a justice of the peace before being sheriff. He had the same J.P. beat, Beat 2, that my great-grandfather James Augustus Hudson had as J.P. in the 1920s.

I ask: Ever hear about executions at the courthouse, or lynchings in this part of Mississippi, in the 1920s or 1930s, ones Mr. Pruitt photographed? He says: Can’t even recall who was sheriff then. Way before my time.

To make sense of Mississippi, I guess for my whole life I’ve roamed America and read many a book, especially the Holy Bible, and listened to the blues. The Pruitt photographs have been key on that journey.

He seems uncomfortable talking about this with me, my mother and his wife standing there. Talk shifts to how he was enjoying my daddy’s 1972 Chevrolet Impala, which he’d bought after my father, Russell Hudson, died. After 20 years, the former sheriff says the car still runs well. He’s using it for his job at the funeral home, seeing people he knew as sheriff including a fellow who walked into the funeral home with a limp, a man he’d put in jail for killing somebody at the High Hat nightclub. The man got life for the killing. Parchman, the state prison, had let him out on compassionate leave to come to his mother’s funeral. The former sheriff says, “Things are starting to loosen up at Parchman.”

To make sense of Mississippi, I guess for my whole life I’ve roamed America and read many a book, especially the Holy Bible, and listened to the blues. The Pruitt photographs have been key on that journey. The last of four boys, I grew up baffled and then ferociously troubled by racial segregation in a town that was in the eye of two hurricanes a century apart: the Civil War and the Civil Rights Movement.

On Sunday mornings, I delivered the local newspaper at the same time the Ku Klux Klan chapter delivered its papers. My daddy’s Main Street Service Station had three restrooms: Ladies, Gentleman and Colored. The station’s motto was “Don’t Cuss. Call Russ.” My brother closest to my age was a sophomore at Ole Miss when two people were killed during the 1962 riot called the Battle of Oxford, amid a national crisis over racial integration. My Sunday School teachers couldn’t explain this. Neither could family nor family friends. Mississippi writers and journalists did, though. Inspired by them, I left the University of Mississippi in 1973 with an undergraduate degree in history and journalism and headed to New York’s Columbia University to study journalism. To use vernacular my Mother hated, I got the hell out of Mississippi.

At Columbia, I reported on Coney Island with its racial tensions among elderly Jews, Blacks, and Puerto Ricans. Over the course of 45 years, I left New York for Oregon, then briefly returned to Mississippi before going to New England, then to Los Angeles, onto North Carolina, Missouri, and back to North Carolina. In the early days, I interviewed the KKK’s national leader and covered a KKK demonstration that erupted into violence in Boston. I wrote about ethnic conflicts in Monterey Park, California, when Asian communities were immigrating to the area.

In these travels, I left Mississippi. Mississippi never left me. Neither did O.N. Pruitt.

Discovering the photographs of Pruitt (1891-1967) helped me gain richer insights into the culture and history that Mississippi writers Kiese Laymon, Richard Wright, John Grisham, and Jesmyn Ward address and what Nobel Laureate William Faulkner called “the human heart in conflict with itself.”

As part of my discovery process, I’ve wanted to share the powerful and exquisite photographs that come from a river town built on cotton and enslavement, making its way in fits and starts through modernity, racial integration, and into the 21st century.

A key moment in all this happened in the 1970s, when two boyhood friends, Mark Gooch and Birney Imes, wanted to show me what they’d found. With them I ascended creaky wooden stairs to a second-floor photography studio on Main Street in Columbus, Mississippi. This was when we were emerging as college-aged photographers, journalists, and folklorists.

Stuffed into pasteboard boxes and wooden crates, tens of thousands of photographic negatives and prints surrounded us. A vinegar smell oozed from off-gassing negatives as we visited with commercial and studio photographer Calvin Shanks, a beanpole of a man. The trove, Mr. Shanks told us, represented four decades of work by his former employer, Mr. Pruitt.

Stuffed into pasteboard boxes and wooden crates, tens of thousands of photographic negatives and prints surrounded us. A vinegar smell oozed from off-gassing negatives.

We asked Mr. Shanks what he planned to do with the pictures. Make calendars, he said — someday. He invited us to look through the boxes. As we sifted through prints and negatives, we were amazed. We realized these deserved to be more than calendar images — they needed to be preserved, researched, exhibited, and published.

Mr. Shanks, who loved a good cigar as much as Mr. Pruitt, declined our entreaties to sell them to us. By 1983, he died. Soon, the collection moved across Main Street to a hardware store and the “knit and stitch” yarn shop operated by Billy Frates and his mother. Billy loved Pruitt’s pictures of locomotive trains so he bought the cache from Mr. Shanks ’s widow. Eventually, he grew tired of fooling with the pictures. After four years of visiting Billy, my friends Mark and Birney, and I — and two others who grew up with us, Jim Carnes and David Gooch — persuaded him to sell us the collection. Eventually, by 2005, we realized the negatives needed a permanent home. We found that at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, considered one of the foremost repositories for materials of the American South.

Between the years of acquiring the collection and transferring it to UNC, we discovered that this collection was one of the most significant of its kind from a small Southern town. Former National Endowment for the Humanities Chairman William Reynolds Ferris describes Pruitt’s photographs as “a national treasure.”

A traveling exhibition sponsored by the NEH ran from February through April 2022 in Columbus. UNC Press, in partnership with Duke University’s Center for Documentary Studies, published my companion book, O.N. Pruitt’s Possum Town: Photographing Trouble and Resilience in the American South. On a cold February night last year, I welcomed the exhibit’s opening crowd, more than 400 people from as far away as Salt Lake City, London, and Boston. Mostly, though, they came from right there in Columbus, Mississippi, population 24,000, which was nicknamed Possum Town by the Choctaw and Chickasaw, based on the face of the local trading post’s manager, Spirus Roach. His wizened look reminded them of a possum’s.

“Slow down and see if there’s common ground, a place where you might discover things about yourself, your neighbors, your friends, your enemies, the people around you,” I told the exhibit’s opening crowd. “[Pruitt’s] images are beautiful…horrifying…uplifting. See who is pictured. Why? Who is not pictured? Why? This isn’t a complete story.… It’s a kaleidoscope…a wide range of images of trouble and resilience.”

Over the years, I’ve discovered the “expressive power” that my mentor Deborah Willis, a New York University professor and global expert on Black photographers, taught me to seek in Pruitt. When I encourage people to join in that search, I quote from my book’s preface: “To research, and to tell a visual story of one’s own people…can be difficult.… I alone cannot tell the stories of Pruitt’s photographs. That requires a collective effort among all kinds of people with all kinds of backgrounds and beliefs…I do not desire to tell anyone specifically what to think; rather I want to suggest what to ponder or, perhaps, to dream.”

To understand how Pruitt fits into the photographic canon, I turn to the words of John Szarkowski, legendary photography curator of the Museum of Modern Art. He wrote: “Photography has learned about its nature not only from the great masters, but also from the simple and radical works of photographers of modest aspiration and small renown.” Indeed, in 1991, Szarkowski met in Birmingham, Alabama, with three of my Pruitt partners—Jim Carnes, Mark Gooch, and Birney Imes — who showed him Pruitt’s photographs. The curator declared that over time these images would age with complex flavors, like a fine bottle of wine, and become only more fascinating.

Pruitt grew up in south-central Mississippi and moved with his wife Lena and their two children to Columbus around 1920 to work for photographer Henry Hoffmeister. To be a photographer then was the equivalent of today’s internet entrepreneur. By 1921, Pruitt bought Hoffmeister’s business. Always with a camera, he took pictures except when he was fishing, hunting, or spending time with family or friends. He was a photography addict. Beyond that, he was an accomplished photographer who trained at the Illinois College of Photography before coming to Columbus.

With large-format cameras, Pruitt documented floods and fires, weddings, carnivals, baptisms, and county fairs. He documented the aftermath of the April 5, 1936, tornado in Tupelo, one of the worst in American history, one that did not kill a toddler named Elvis Presley, and one for which Pruitt photographed a makeshift morgue of Black victims. Pruitt recorded the 1952 visit of Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright and native son Tennessee Williams. He photographed a stone monument — I daresay among the few Civil War-related monuments in Mississippi that is dedicated to both Union and Confederate soldiers who fought the Battle of Tupelo. Pruitt regularly photographed Dr. Emmett J. Stringer, who in 1954 served as president of the Mississippi chapter of the National Association for Advancement of Colored People and whom the KKK listed as a target for assassination.

With subjects on front porches, in backyards, living rooms, kitchens, and furrowed farm fields, Pruitt photographed everyday life. In his studio, he did most of his work. Musical groups with instruments, girls in fancy dresses, boys in cowboy boots, men with starched white shirts or overalls, ladies in dresses with lace collars, families in Sunday go-to-meeting outfits or Army Air Corps pilots dressed in uniforms glinting with brass — they trekked up Pruitt’s stairs. His portraits compare to the best big-city, celebrated photographers.

“It’s a portrait of everything Walt Whitman was talking about…. It’s ‘this is America’…here we are, the whole crazy experiment sitting for its portrait.”

Many readers who live in a Facebook or Tik Tok world may find this hard to comprehend: Grown-ups and children alike, in the 1920s and 1930s, never had been photographed before Pruitt made their pictures.

His range of beautiful portraits relate to curator Szarkowski’s comment about a Walker Evans photo from 1936, a window display of pictures at a studio in Savannah, Georgia. “It’s a portrait of everything Walt Whitman was talking about…. It’s ‘this is America’…here we are, the whole crazy experiment sitting for its portrait.”

Pruitt’s everyday images gave no full indication of his work’s scope until we followed Billy Frates’s suggestion to contact Mrs. Shanks about secret negatives, ones she held back from what she’d sold him. Eventually, we acquired those. They had no information about the events or people depicted. Before Google, I spent years to discover: At the Lowndes County Courthouse in the 1930s, Pruitt documented separate executions of two Black men, among the last public executions by hanging in the nation. In a Black churchyard, he photographed in 1935 the bodies of two young Black farmers who had been lynched.

For my four friends and I, each of us white, seeing those brutal photographs transformed how we approached the images, some purposefully hidden, never shown to us or our town in any public way.

As part of the research, decades ago I went to the courthouse and met with an elected official, a white man. I asked him if he could help me find information about executions or lynchings. He said he’d never heard about those. Then, sotto voce, he said, “There are some people now that could use a good hanging.”

Flabbergasted, I shook my head, and left his office and went to the archives, where I ran into a friend, an attorney, who helped me search court records. I discovered filings about the 1934 trial of James Keaton, charged with killing a white service station manager. John C. Stennis was the prosecutor. (Stennis, who was photographed by Pruitt, would become one of Mississippi’s U.S. senators, known for his staunch support of racial segregation. In recent years, his granddaughter, Laurin Stennis, created an alternative to the Mississippi flag by removing the Confederate stars and bars.)

Keaton’s defense attorney requested that the judge instruct the all-white, all-male jury this way:

Gentlemen of the jury, the Court instructs you that Mulattoes, negroes, Malays, whites, millionaires, paupers, princes, and kings, in the courts of Mississippi, are on precisely the same and exactly equal footing. All must be tried on facts, and not on abuse. Only impartial trials can pass the Red Sea of this court without drowning. Trials are to vindicate innocence or ascertain guilt.

The judge refused. However, three decades earlier, citing similar language, the Mississippi Supreme Court had reversed the murder conviction of a Black man.

Convicted, Keaton was executed. Pruitt photographed a gallows scene with white law enforcement officials around Keaton, a thick rope encircling his neck. Afterwards, Pruitt photographed underneath 19 white male spectators surrounding Keaton’s body, a black hood over the head.

Another troubling set of Pruitt photographs documented the July 15, 1935, lynching of Bert Moore and Dooley Morton, accused of harassing a white woman at her home. A mob of three dozen white men had overtaken a deputy’s vehicle with the young men in it. Taken to a churchyard miles away, Moore and Morton were lynched. The sheriff called Pruitt to photograph the bodies.

Soon, that picture served the purposes of white supremacists and the Black press. The country’s major Black newspaper, the Chicago Defender, published the image on its front page under the caption, “White Civilization.” The image also became what’s known as a lynching postcard. In the 1960s, the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission objected to the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee and civil rights activists using the image to “besmirch” the state’s image. Since then, the photograph has appeared in documentary films.

Brutal or sublime, the Pruitt photographs create a “photobiography,” one that links to stories and photographs around the world, including those grounded in the Jim Crow era of racial-segregation laws enacted in the late 19th century.

Whether I’m looking at historical photos of racial violence, Facebook birthday party photos or a framed picture on a bedside table, I’ve learned from photographic scholars what common sense tells us: Each of us interpret photographs distinctly. We experience them differently at different times. It helps to know the who, when, why, how, what, and where. Still, as the poet William Carlos Williams observed in 1938 after seeing Walker Evans’s photographs at the Museum of Modern Art: “The pictures talk to us. And they say plenty.”

Pruitt’s pictures say plenty, too.

After finding Pruitt’s photographs, my job was to provide context, explanations. But that was difficult work. Author James Agee wrote in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), the book that recounted his 1936 journey with photographer Walker Evans to Hale County, Alabama, to document the Great Depression for Fortune magazine, that “fragments of cloth, bits of cotton, lumps of earth, records of speech, pieces of wood and iron, phials of odors, plates of food and of excrement” could have done a better job than his words.

In Pruitt’s photographs, we can see, hear, taste, touch, smell and feel. To that end, the public response to the Pruitt exhibit and book has amazed me. Even today, when common ground seems illusive, viewers of all stripes find ways to enter his images.

At the Mississippi exhibit, a woman used a magnifying glass to look, one by one, at people attending a Church of Christ tent revival. At a Missouri exhibition, photographs reminded a viewer of their homeland of Brazil, a country which for more than three centuries brought from Africa millions of enslaved men, women, and children. A man from Syria looked at the Pruitt pictures and found connections with his life in the Middle East. A third-grade teacher in Missouri asked her students “to find the soul” of a 1930s photograph of a girl with a live rattlesnake. With crayon and pencil, a third grader fashioned on paper the image of a rattlesnake and wrote: “She’s not scaired of snakes. I’m scaired of snakes.”

On April 8, 2022, in a notebook for people to record impressions, someone anonymously wrote a haunting response to two exhibit photos: one, a Black boy with a bloodied nose, surrounded by a crowd of children and grown-ups, the other, an image of three generations of Blacks picking cotton by hand. The feminine, cursive script indicates the handwriting perhaps of an older woman.

“The art is very versatile…the ones I didn’t like was the young boy with the bloody nose. I see it as a ‘picnic’ back in the day.”

“Picnic” was a term describing the public spectacle of lynching Black men in front of white audiences, who sometimes would bring picnics. She continued:

“I understand the concept of the cotton picking from a photographer point of view. However, growing up on a farm & having to pick cotton from sunup to sundown and getting paid eighty cent a day—brought back too many painful memories including a backache that I’m suffering with until the moment I put the pen down.”

Here are discoveries from the archives. Before Google, house to house in Mississippi I would show captionless photographs in search of answers. Or I’d search pages of the local Commercial Dispatch or microfilm copies of newspapers from across America.

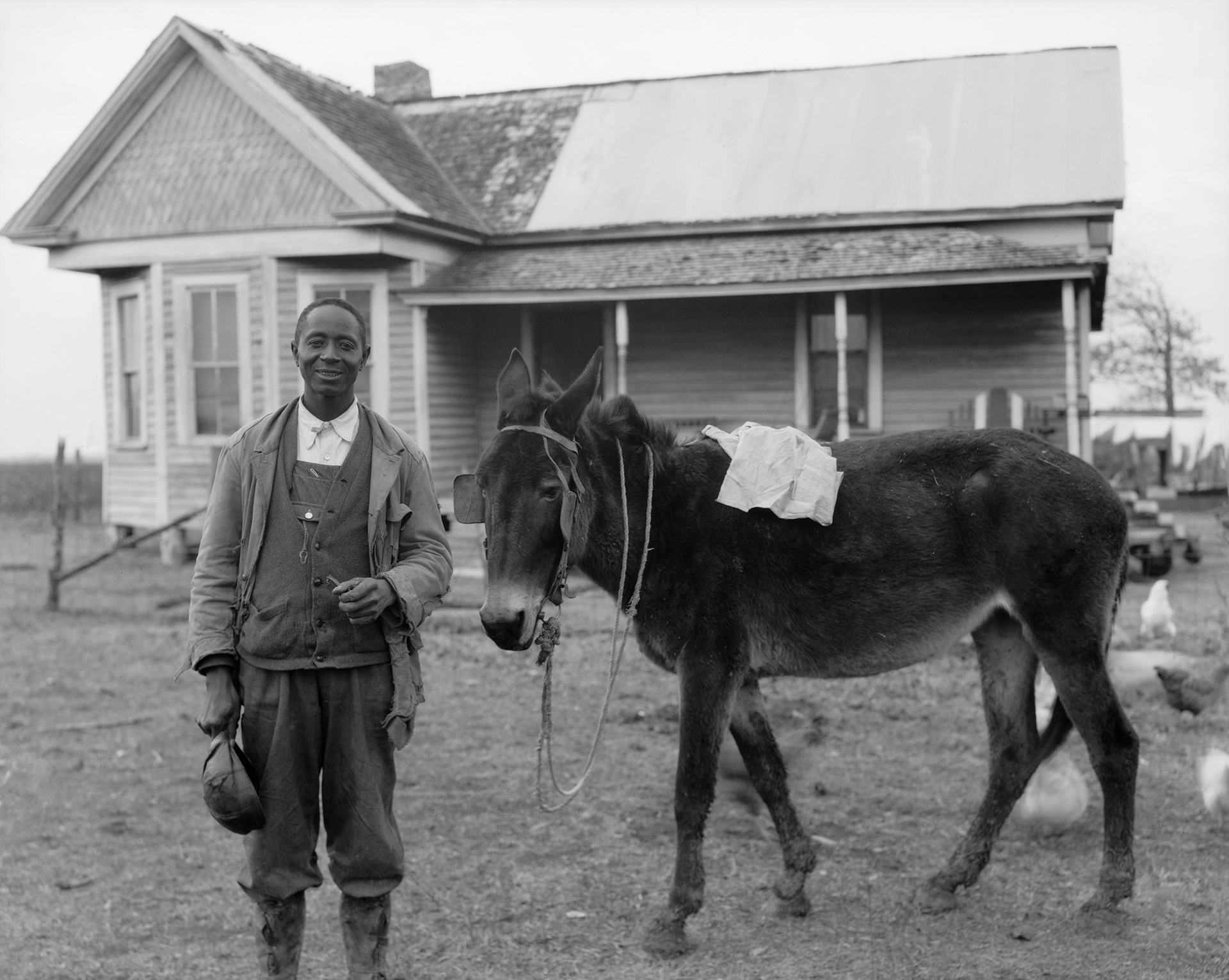

Why did Pruitt photograph a man with a mule outside a farmhouse?

During the Great Depression, Sylvester Harris, a Black farmer, could not pay his mortgage to the federal Home Loan Bank. He and his brother owned about 130 acres in Lowndes County. Inspired by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s fireside chats to boost the nation’s spirit, Harris drove into town to call the president. After 90 minutes on a pay phone, Harris reached Roosevelt, who agreed to help save the farm. Pruitt later took a photograph that, in today’s parlance, went viral. Blues singer Memphis Minnie commemorated Harris with “Sylvester and His Mule Blues.” Newsreels told the story to millions in movie theaters across America. The white press brought Harris’ story to the country’s attention. But the Black press, such as the Chicago Defender and Ebony, truly celebrated Harris as a spunky folk hero who brought hope in a time of uncertainty.

Heavyweight boxing champion Jack Dempsey poses amid a semicircle of white men in dark business suits and hats, surrounded by pines at Lake Norris Fishing Club. With them, a woman is dressed in a white robe and turban. By her, a similarly dressed man is ensconced in an upturned wooden coffin, before a grave in the earth. This is the Great Pasha and Madame Flozella. There’s also a woman dressed in black and a man in a white hat and owlish glasses.

One of my partners, Jim Carnes, realized that was Truman Capote’s mother in black, and, lo and behold, the man with the white hat was Capote’s father, Arch Persons. Research about the November 1930 image unspooled a tale of Pruitt’s subjects coming to Columbus, how Capote’s mother had an affair with Dempsey and Capote’s father managed a buried-alive act. Later, in October 1949, Harper’s Bazaar magazine would publish a Truman Capote short story, “A Tree of Night,” focused on a strange, buried-alive carnival act traveling the American South.

A set of Pruitt photographs of baptisms prompts this suggestion: Gather your relatives and ask them what stories they’re reluctant to tell. Pruitt made pictures on the banks of the Tombigbee River of baptisms by a Black church group and a white church group, at the same time and place. There are many photographs of baptisms. Yet it’s unusual to see a measure of biracial harmony in the name of Jesus Christ depicted alongside a riverbank.

I showed the baptism photographs to my mother when she was in her 80s. Of course, she said, she knew about this but hadn’t mentioned it. She, her brothers, and sister would go to riverbank, three blocks from their home — hardly five blocks from where I grew up — and watch the baptisms. She’d never thought much, she said, about how this happened in a time of racial segregation. Yet my finding these photographs deepened for me the complexity of Mississippi race relations.

When Tennessee Williams returned in May 1952 to Columbus with his grandfather the Rev. Walter Dakin, Pruitt photographed them with banker and lay Episcopal leader Davis Patty at Patty’s home. In a May 9 letter, the playwright apparently included a newspaper photograph published of him and his grandfather during the visit. Williams wrote from Columbus’s Gilmer Hotel: “…[W]e have arrived in my point of origins on this unhappy planet…[T]his evening I am going out with one of our elegant Aunties, a Mr. Patty, to a big lawn party on a plantation called Sugarlock. He said the company would not be appropriate for grandfather, so grandfather is dining elsewhere. I guess it’s a ‘gay’ plantation…The [Columbus] homes, the interiors, are just incredibly beautiful, almost everything in them is a priceless antique. But the people’s ideas are older than the furniture…it is a strange part of the world and I feel as if I had always known it…”

At the Pruitt exhibit opening, I told the group: We move too fast. We need to slow down. Look. Listen.

Later, a quite upset woman approached me and introduced herself as Jan Ellis. She said she’d not heard about the exhibit until she and her husband Allen were driving on Main Street and saw six Pruitt images filling the windows of the Columbus Arts Council gallery. They’re beautiful, she said, of three portraits of white people, three of Black people.

Now, she told me with a swirl of exhibit goers around us, you’ve ruined the whole evening with the lynching photograph. “Why didn’t you show photographs of white people being lynched?” she, a Black woman, asked.

I asked if she saw the sign outside the curtained off area with the lynching image: “This section…includes…depictions of racial violence, including lynching. If you prefer not to view this content, please continue to the next section.”

Yes, she said, she saw it. But she and her husband entered, and that ruined everything.

I said I’m not an expert on racial violence’s history but I’d spent years researching that. I told her I’d met with and received support from lawyer Bryan Stevenson, and that he founded the Equal Justice Initiative, created the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, and wrote Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption, a New York Times bestseller. Stevenson’s efforts to honor lynching victims were documented on a CBS News program hosted by Mississippi-born Oprah Winfrey. I learned from Stevenson, I told her, about the importance of including images of racial injustice in combination with images of Southern culture’s enduring resilience and grace, both Black and white. Acknowledging this, Stevenson has said, is how we understand our history and overcome our past.

Still skeptical, she said she’d telephone a preacher friend of hers in Ohio and that he’d agree with her, that displaying Black violence contributes to Black trauma and solves nothing.

I told her I was leaving town soon, but we could meet again. She agreed that’d be good.

The next morning, I was walking on Main Street. There was Jan Ellis. She’d spoken at length with her preacher friend. He told her we need to acknowledge racial violence and lynching, even if that means displaying excruciating images. She now understood, she said, why the exhibit included images of violence along with pictures celebrating the community life of Blacks and whites alike. I invited her and husband to come to a panel the next day.

At the panel, a standing-room-only crowd of 125 gathered, one-half block from where Pruitt had his studio. In a hybrid event with two of my project friends, Jim Carnes and Mark Gooch, Zooming from Birmingham, Alabama, and with Birney Imes, David Gooch and myself, we offered observations. As moderator, novelist Deborah Johnson, who as a Black woman has written about race in Mississippi, guided us to think deeply about the photographs.

After about 75 minutes, a man in crisp overalls and a ball cap sewn with “I ❤️ Jesus” on it, rose. It was Allen Ellis, Jan’s husband, age 91, and someone people had told me was a local street preacher.

He didn’t have a microphone, so it was hard for everyone to hear. I asked him to speak louder. As he did, it became clear the photographs prompted him to offer that moment as an altar call after a Sunday sermon, to ask people to accept Jesus Christ as their personal savior. He quoted from John 3:16.

So everyone could hear, in call and response, I repeated...

“For God so loved the world…”

Back and forth, we continued.

With that, a benediction occurred. People then made their way among the scores of Pruitt framed photographs, to see, taste, smell, touch, hear, feel, discover.

About the author

Berkley Hudsonisanemeritusassociate professor of the Missouri School of Journalism, where he taught from 2003 to 2019. For 25 years, he worked as a newspaper and magazine journalist for theLos Angeles Times, among other publications.From 2015 to 2017, he was founding chair of the University of Missouri’s Race Relations Committee. For that work, he received the University of Missouri System’s President’s Award for Service. At the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, he earned a doctorate in mass communication with a certificate in folklore. In partnership with Duke University’s Center for Documentary Studies, UNC Press published his book O.N. Pruitt’s Possum Town: Photographing Trouble and Resilience in the American South (2022). That book, the subject of this story, won the 2023 Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters Award for Life Writing. O.N. Pruitt’s Possum Town also serves as a companion to a National Endowment for the Humanities traveling exhibition of Pruitt’s photographs. Hudson and his wife Milbre Burch live in Chapel Hill. Together, they oversaw the Storytelling Project of the Cotsen Children’s Library, affiliated with Princeton University.

Wonderful essay!! Sounds like a must-have book.

Berkley, bravo! Only you could have responded in the way you did to the benediction offering. Congratulations for using the genuine YOU in such a beautiful way.

Mimi