Hope Is a Place

Marianne Leek went to interview 87-year-old David Burch in North Carolina. She thought it would last an hour. But it lasted all day. And she learned a lot of lessons about hope.

“Our welfare simply is wrapped up in the welfare of the other, and we do not have a choice about it. Isolation and loneliness in communities is the death of them. A truly common life is something worth nurturing, and it demands attention and effort.”

— from “Marcus Mumford on John Steinbeck’s ‘Lessons in Justice and Power’”

I am a career educator. I have taught in western North Carolina for 30 years. When you teach in small, rural communities, you often teach entire families.

During my career, I taught several of the great-grandchildren of Guy and Nina Burch. In February of 2020, I received phone calls from two of their granddaughters, who asked if I would interview and tell the story of their dad, David Burch, the son of Guy and Nina Burch.

When Burch’s daughters called me about the possibility of talking to their Dad, I wasn’t sure what to expect. I arrived at 10 in the morning, figuring I would stay an hour. I did not leave until mid-afternoon.

While the Burch family is just one family, in many ways they represent all families, especially those from Appalachia in the wake of the Great Depression. The survival of the American family is and will always be dependent upon the love of neighbors and the collaboration of community. As the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. once reminded us, “What affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

People sometimes describe those who survived economic hard times such as Appalachian poverty or the Great Depression as “coming from nothing.” Oftentimes these same people will describe themselves as “self-made.” These are both misnomers. After talking with David Burch, I know this to be true: No one comes from nothing and there is no such thing as being self-made. One life continues to pour into another, generation after generation, even if the family moves itself thousands of miles from the place they called home.

If you turn onto Burnt School House Road in Hayesville, North Carolina, you might see a tiny house sinking in on itself, hidden behind fallen trees and briar thickets, but not yet entirely consumed by the creeping Kudzu. To David Burch’s family, it is a reminder of where they come from and to whom they belong. Those broken walls are a visual ode to a time when they abandoned the familiar, only to discover that sometimes hope can be found in a place.

After the completion of the Chatuge Dam in 1942, the Tennessee Valley Authority left the rural communities of Towns County, Georgia, and Clay County, North Carolina, taking with it one of the few opportunities in Appalachia for viable employment. Following the departure of the TVA, the area quickly returned to the economic wasteland it had been, leaving the people in these communities without the support necessary for them to meet their basic needs.

Subsequently, many residents were forced to relocate to find work and feed their families. Some followed the TVA to other dams. Others went north to the steel mills and automobile plants. And some moved clear across the country to work in the logging industry. The family of Guy Burch was one such family. The road to Ryderwood, Washington, and the five years they spent there changed the way this family viewed their place in the world, broadened their thinking, broke a cycle of poverty, offered them hope, and changed their trajectory for generations to come.

“The truth of the matter is, we almost starved to death. There was nothing here. It was hard to make a living. My dad had six kids. There were no opportunities."

The Journey West

Working for the TVA had afforded Guy Burch the opportunity to save enough money to rough in a small home on four acres in what remained of the unincorporated community of Elf in Clay County. The land came to him from his father, deeded to Guy for $1 with love and affection. The home put a roof over his family’s head, but it was just 700 square feet without electricity or a water supply.

By 1946, Guy and Nina Burch and their six children were barely surviving. Their eldest child, David Burch, now 87, was in sixth grade at the time, part of the first class of the new Elf school, which was rebuilt by the Works Progress Administration after the original structure burned down.

“The truth of the matter is, we almost starved to death,” David Burch says today. ”There was nothing here. It was hard to make a living. My dad had six kids. There were no opportunities. There was no defense contractors. There was no assets here. There was no money. There was no plants.”

David Burch says it was difficult not only for his own family but most others during this time.

“My mom was a strong woman, but when you think about it, women didn’t stand a chance,” he says. “There weren’t no sewing plants. There weren’t no jobs for women, unless you was a school teacher. If you was 31-32, with six children, what was you to do?”

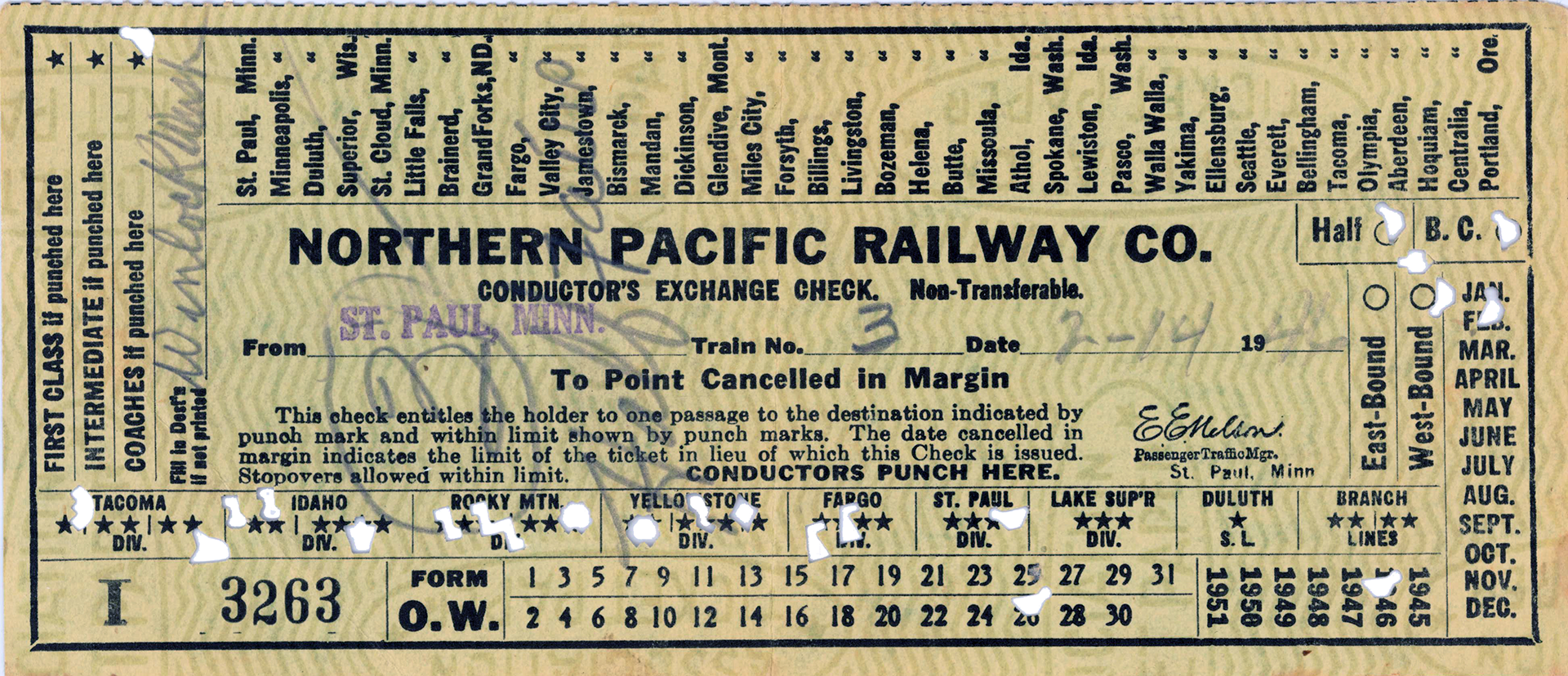

Then, his father Guy was recruited by the Long-Bell Lumber Company, the second largest lumber company in the U.S. He sold his small home and property for $700 and used that money to purchase train tickets for the family of eight to make the journey across the country to Ryderwood.

“My dad had his problems, but he was adventuresome,” says Burch who now understands the weight of his father’s decision and his mother’s apprehension. “In 1946, when you left North Carolina to go to the state of Washington, you weren’t coming back. He had to be progressive.”

Their cross-country journey began with this family, which did not own a vehicle, finding a way to make the 50-mile round trip to Murphy, North Carolina, to purchase train tickets.

Their neighbor O.A. Blankenship, who owned a truck, had agreed to take them from Elf to Knoxville, Tennessee, to board the train. At 5 a.m. on February 13, 1946, in the light of a winter moon and dimming stars, Guy Burch and five of his children climbed into the bed of Blankenship’s 1942 Chevrolet pickup truck lined with hay and covered by a makeshift tarp. Nina Burch and their 3-month-old son squeezed into the cab with a friend, Lassie Ledford, O.A. Blankenship, his wife Sue, and their infant daughter. The Chevy full of 12 people began a 130-mile drive to Knoxville, Tennessee. This family would travel most of the day in the middle of winter, through Cherokee and Graham Counties, across the Tail of the Dragon, and finally down into the Tennessee Valley before arriving at the train station in Knoxville late that afternoon.

Their winter train trip across the country aboard the Northern Pacific Railway would be just the final leg of an arduous endeavor.

“My family joked at the time that they would have to blindfold us kids to get us on the train. We had never seen a train,” David Burch said. “We didn’t have no electricity to listen to a radio or any communication at the time to know what a train was.”

A Completely different Life

In anticipation of the journey, Nina Burch had prepared and packed fried chicken, hard-boiled eggs, bread, and other food to sustain her family for four days and nights by train. David Burch and his sister Helen Burch recall a dining car, but that was a luxury they couldn’t afford.

“At night our dad took two suitcases and put them in between the two double seats, which faced each other, to make beds for the children,” Helen remembers. “We also had a few quilts with us to use for beds.”

“I don’t believe we slept much the first night due to our excitement. The train was noisy and made frequent stops,” she says. “At night the lights from the cities we passed looked just like Christmas. Remember, we did not have electricity when we left our home.” She also recollects her mother bathing the youngest children in a sink of a train station and washing out cloth diapers for the baby in the restroom during a layover in Chicago. The other children were able to wash up by taking a “bird bath” in the sink of the same restroom.

Late in the afternoon of February 17, the family finally arrived in Ryderwood. Upon disembarking from the train, their mother looked at her husband and asked, “Guy, now what do we do?”

David Burch explained his mother’s initial reaction, “No one knew we was comin.’” The Burches made their way to the home of Boss and Bertha Cothren, a family from Clay County who had relocated to Ryderwood's logging town.

“We knocked on the door,” David remembered. ‘There we stood, a man and his wife and six kids, but they hollered, ‘Come in.’ Bertha, bless her heart, said, ‘Yuns had anything to eat?’ We said, ‘No.’”

The family took the Burches in, fed them, and made pallets on which they could sleep.

The next morning, Landon, their host’s son, closest in age to David, said, “David, I’m going to school. You wanna come with me?” On the way to school, a classmate of theirs, confidentially informed David, “Our teacher is from Oklahoma. Her name is Mrs. Kilgore, and she thinks she knows everything.” Despite this initial description, David fondly remembers all of his teachers in Ryderwood, especially Mildred Kilgore and her husband Haston.

“The teachers were good and a good teacher is worth a million dollars,” Burch says. “The teachers were from all over the country. Mrs. Kilgore read Uncle Tom's Cabin to me in the sixth grade. This affected my thinking for the rest of my life. Mr. Kilgore was the principal of the elementary school and a good teacher. He taught us penmanship: cursive. We used a dip pen when learning how to write. He believed that penmanship was important, that it was a signature of one’s intellect and personality. They also taught us mechanical drawing. The best teacher I ever had was also our football coach. He was a history and English teacher. He was real strict. He read the Canterbury Tales with us and had us translate the prologue from old English to modern English. He’d embarrass you if you didn’t have your lesson, but you’d wanna work hard for him. He taught English literature, and he would tie history, literature, and religion all together. You can't teach those things in isolation and do a good job. He had a great influence on my thinking.”

David Burch firmly believes environment shapes a child. When he left Elf, he was in sixth grade and said the school had attendees from all socioeconomic levels. “There is always some kids more affluent than others, but when you’re in the low end of that scale — which we were — your environment has a lot to do with how you behave and react.”

Like the scene from To Kill a Mockingbird when Scout’s first-grade teacher Miss Caroline Fisher sends Burris Ewell home for having lice, David Burch recalled teachers in Elf checking students’ heads and sending them home if they found lice. He says, “They’d get us and check our heads and you was ashamed.”

However, that changed in Ryderwood. The Burch children attended the logging town’s small 1-12 school, which served approximately 100 students.

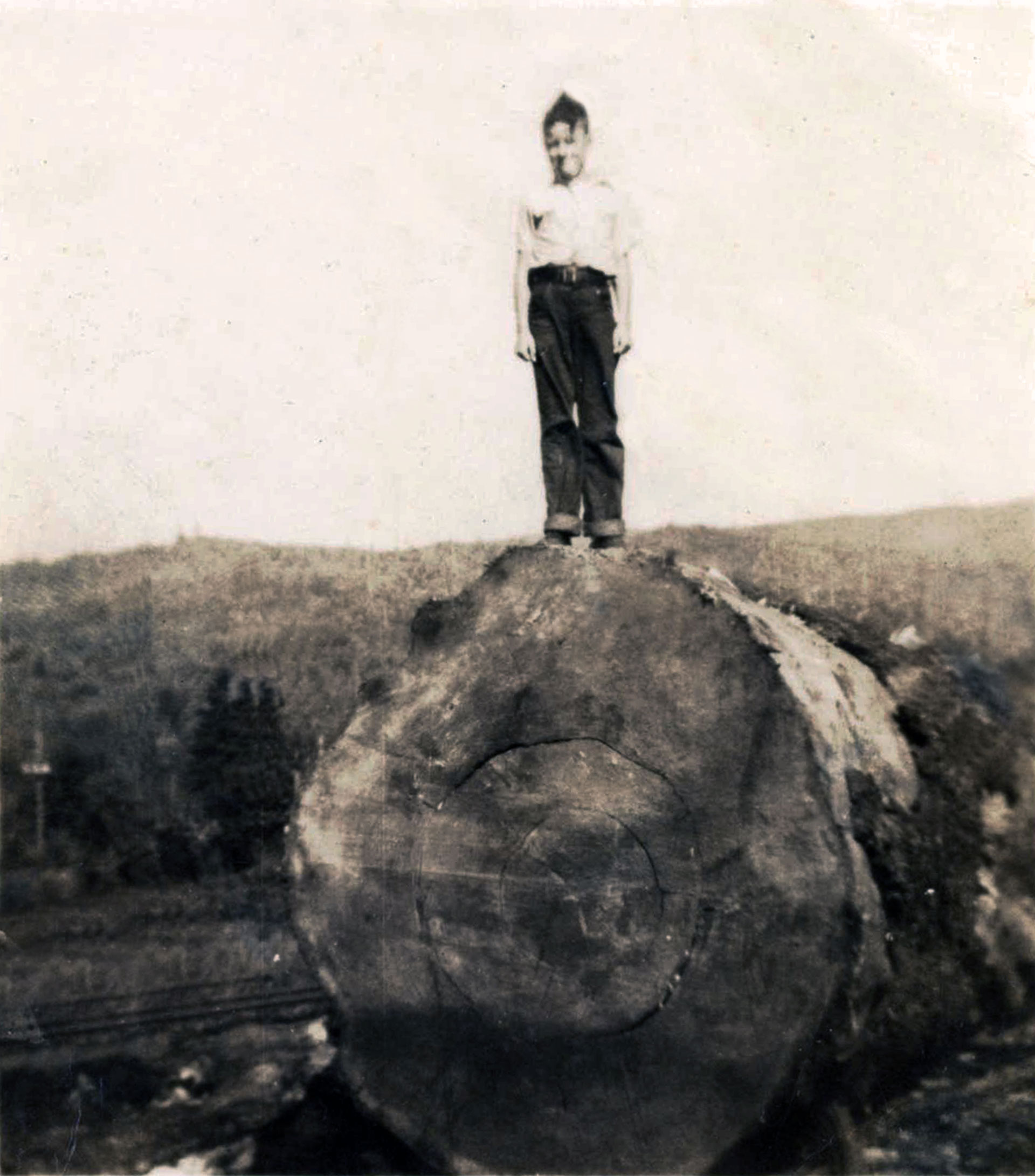

“Everybody in the town was a logger,” David says. “Economically, I was suddenly just as important as any kid in that school. We all lived in company housing. We was all kids of loggers. I was just as important as anybody else. That makes a difference in the mind of a child. I wasn’t a second-class citizen anymore. You know what, though? After we moved to Ryderwood, we never had lice again. Our environment had changed.”

After the first day of school in Ryderwood, David Burch returned home and discovered to his surprise that their dad had already “rented a house, got a cookstove, a refrigerator, and our mama was cookin’ supper. We had electric lights. People had given them stuff. We never looked back.”

Daily life in Ryderwood was completely different.

“Just gettin’ firewood in Elf had been a full-time job,” David says. “In Ryderwood they had all the wood we needed for the stove. When we moved there our life changed. We had electricity. We had running water. My dad had a job. “

In a matter of one week, his life and the circumstances of his family had changed dramatically. In addition to the obvious housing differences, the family dynamic had also changed.

This was not lost on young David Burch.

"We thought we'd gone to heaven"

Ryderwood was one of the few planned logging towns in Washington. In 1923, the town was designed and built by the Long-Bell Lumber Company as an alternative to logging “camps” in which men lived for a time while logging in the woods. The intention was to build a town for loggers and their families in an effort to provide a more stable environment, and 1923-1953 the logging town did just that. In addition to its commitment to providing a stable environment for logging families, Long-Bell Lumber Company was progressive in its conservation plan and implemented a reforestation initiative, establishing a forest nursery in Ryderwood. According to the Ryderwood History Project, this nursery provided “plant stock sufficient to complete the stocking of three to four thousand acres of land annually.”

It had a general store, a school, a movie theater, a post office, a nondenominational church, a cafe, and a tavern (a hotel for the single residents of the town).

The company store also gave families food and supplies on credit (later deducted from a worker’s paycheck) so Nina Burch could purchase enough food for her large family.

“It gave the mom an opportunity to feed her family regardless of what the husband did,” Burch says. “We could go to the movies. We could get ice cream. We could get cokes. You take a kid that was starvin’ to death, didn’t have water, didn’t have electricity, move them into that environment … we thought we’d gone to heaven.”

As he entered his teen years, David Burch found himself employed, sharing a paper route with one of the other boys in the Ryderwood community.

“I was responsible for delivering papers on one side of the street and him the other. I got paid $2 a month,” he says.

David Burch later took on the other side of the route and earned $12 a month, which he used to buy a bicycle. “It was a used blue bicycle that I got for $10. I paid payments for a couple of months till I had it paid for. It gave me an opportunity to better my circumstances.”

During the first three years the Burch family lived in Ryderwood, Guy Burch quadrupled his North Carolina salary. The family lived in company housing with electricity, running water, and an indoor toilet. The children enjoyed a rich academic and social life. They made friends and rode their bicycles throughout their neighborhood. After a couple of years, the family could financially move into a bigger company home, where they cultivated a large garden, as well as owned a cow and hog. David taught the young people of Ryderwood how to square dance, something that would not only catch on in Ryderwood but would also carry over to the neighboring town of Longview. In many ways, the time this family spent in Ryderwood was a beautiful exchange of the very best of regional traditions and culture in a small, rural, community that included hard-working people who migrated from across America.

In 1949, the lives of Guy and Nina Burch and their seven children were abruptly and tragically changed. Guy Burch was a passenger in a head-on automobile accident that left him permanently disabled and no longer able to work and provide for his family. Thus began two years of rehabilitation and a community taking care of its own. Guy Burch’s father was a widower who made the trip out to Ryderwood from Hayesville to help take care of his son and his son’s family. At the time of her husband’s accident, Nina Burch was pregnant with their eighth child. David was 15 at the time.

“It was before the [Americans with Disabilities Act] and Social Security … ... the only recourse a person had in those days was welfare,” he remembers. “Mr. McDonald was a man who worked in the woods, but he also operated Ryderwood’s theater. I remember him telling my mama, ‘I can’t do much for you as a family, but I can do this — your kids can go to the movies for free.’ There was groceries that come to our house and we never know’d where they came from. I guess that’s why I’m the way I am now.”

David Burch’s grandfather came and lived in Ryderwood and found work as a section hand maintaining a seven-mile stretch of tracks on which the locomotive traveled from Ryderwood to Longview. He worked to help support his son’s family for two years before deciding it was time for the family to return to North Carolina.

The return was like stepping back in time for the eldest Burch children who had become accustomed to their progressive circumstances. David remembers the difficulty of coming home in 1951: “no opportunity, no running water, and back to a school where I found it difficult to fit back in.” He explained, “I went from going to school with around 25 other boys that I was an equal with, to a school with more kids. My social life was nonexistent. I lived seven miles outside of town in Shooting Creek and we didn’t own a car. I had no way to do anything. We moved into a house that now had electricity, but we had to go back to hauling water from the spring at the bottom of the hill.”

His family had returned to a life of barely surviving.

Upon graduating from Hayesville High School in the spring of 1952, David Burch once again made the journey across the country to work for the Long-Bell Lumber Company in the neighboring town of Longview, Washington. However, not long after, the Long-Bell Lumber Company decided to close its mill and sell what remained of the town of Ryderwood. I ask David Burch why he never considered permanently relocating to Washington.

“Because family was here and here was home,” he replies. Burch worked to put himself through school at Young Harris College, at the time a two-year college in north Georgia, attending night classes five nights a week and paying $90 a quarter for his education. He worked for and eventually retired from the United States Postal Service, but the time he spent in Ryderwood continues to color his entire existence and to influence how he treats others.

The Thing About Place

Before my talk with David Burch ended, I found myself seeking his wisdom about the state of modern society. He said, “I think it’s good that we have access to so much more information, but now we have access to too much information. I don’t think people read enough today.”

He brought up his former English teacher and coach from Ryderwood who had such an influence on his thinking.

“Back then there were three ways to get information: Time, U.S. News & World Report, and Newsweek — print magazines,” Burch said. “All three of these publications had different viewpoints — they was biased. They had different ways of presenting information. Not none of them necessarily right, just different ways of reporting what was going on. The difference was, our teacher taught us to read each of them, consider the different points of view, and to think for ourselves. People just don’t do that anymore.”

As I was leaving the home of David Burch, he handed me some papers about the logging town of Ryderwood. When I arrived home, I noticed that he had accidentally handed me an unpublished essay written by James Allen Wood, a teacher who also served as the principal of Elf school during the 1925-26 academic school year, 20 years before David Burch attended Elf school. After his time at Elf school, James Allen Wood went on to practice law for over 60 years and became a judge in Corpus Christi, Texas.

“Back then there were three ways to get information: Time, U.S. News & World Report and Newsweek — print magazines. All three of these publications had different viewpoints — they was biased. They had different ways of presenting information. Not none of them necessarily right, just different ways of reporting what was going on. The difference was, our teacher taught us to read each of them, consider the different points of view, and to think for ourselves. People just don’t do that anymore.”

The essay described how after graduating from Lipscomb University in Nashville, Tennessee, Wood got his position at Elf school. He wrote about his three-day journey by train and automobile to get from Nashville to Clay County — via Nashville to Chattanooga, Chattanooga to Knoxville, Knoxville to Asheville, Asheville to Murphy, and finally Murphy to Hayesville. Today, by car, the same trip would take no longer than four hours.

Upon his arrival to Clay County, Wood met with Allen J. Bell, the superintendent of schools, who informed him that he would need to complete the last part of his journey to the Elf community on foot. About this Wood wrote, “He told me that Elf was six miles away and unless you had a horse, buggy or wagon, the only way to get there was to walk. It was a warm, sunny day and the final leg of my trip was by that method, which I didn’t mind at all.” This principal lived in the home of a local family for a year. He was 19.

Of his year in Elf, over a decade before the TVA would begin work on Lake Chatuge and the Chatuge Dam, Wood wrote, “It was a land of beauty, a land of peace, a land now of the unreturning past, a land of one church, one school, one store, a land where government was irrelevant … a land of no rebels as there was nothing to rebel against, a land of permanence, where time seemed to stand still. There must have been a sheriff and a county judge, but I never saw or heard of them. The state must have had a governor, but I have no idea who he might have been. A land of now unimaginable freedom.” He described the effect that living in the Elf community in 1925 had on him by making a comparison to Alfred Lord Tennyson’s poem, ”Ulysses.”

“Tennyson was right when he said, ‘I am a part of all that I have met.’ I am a part of Elf, or at least the Elf that was, and Elf is a part of me.”

Much of the community this former teacher and principal described is now underwater.

And that’s the thing about place. Like creeping kudzu quietly swallowing up the past, the places we call home, for however short a time, become part of us, the tendrils of memory and experience infinitely intertwined.

To David Burch and the older Burch children, Ryderwood was the place that offered them hope, a place that revealed to them what they were capable of and what they could become. Both Elf and Ryderwood would forever be part of each of these eight children. The lasting impact of their time spent in Ryderwood on the trajectory of the Burch family is not lost on any of them. Now, surrounded by children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, this generation of siblings can see the effects of those years manifesting itself in the lives and contributions of their descendants. All eight of Guy and Nina Burch’s children went on to graduate high school and some attended college. The following two generations also all completed high school, most of them completed college, and many have completed advanced degrees. There is no doubt that there is a transforming power in unconditional love and opportunity omnipresent in continued education.

I think about the words of David Burch, “If you can change a child’s environment, you can change their life. If you can change a child’s environment, you can change how they see themselves. You never go wrong when you invest in a child.” And then I think about the words of Marcus Mumford in February 2020 as he reflected on the literary works of American author John Steinbeck, almost 74 years to the day after that cold winter morning when the Burch family climbed into the back of that old pickup truck and headed toward the unknown.

And I think about James Allen Wood, the 19-year-old who, in 1925, traveled to rural Appalachia to live in the home of strangers who became his family and to teach children in a place that for a year became his home.

Mumford, a songwriter and the lead vocalist of the folk band Mumford & Sons, writes, “Our welfare simply is wrapped up in the welfare of the other, and we do not have a choice about it. Isolation and loneliness in communities is the death of them. A truly common life is something worth nurturing, and it demands attention and effort.”

In 1946, in the isolated community of Elf, North Carolina, in the wake of the Great Depression, many families were barely surviving. In Ryderwood, the people of a small, rural community worked together to provide what was essential for all, offering hope to the people who lived there for the three decades that the Long-Bell logging town existed. And the children of Guy and Nina Burch would carry that hope with them to the places each of them would eventually settle and come to call home.

Marianne Leek dedicates this article in loving memory of Johnny Burch who passed away on June 19, 2020, beloved son of Guy and Nina Burch and brother of David, Helen, Juanita, Margaret, Ronnie, Danny, and Alecia.

About the author

Marianne Leek is a retired English educator who teaches part-time in western North Carolina. She contributes frequently to Salvation South and her work has appeared in Our State, Okra, Good Grit, Plateauand WNC Magazine.