Holding on for Dearest Life

Among jellyfish, one species fights like a warrior. Months after one attacked her, she found the lesson it had taught her about scrapping until the final moment.

I was attacked by a jellyfish a few summers back.

I don’t mean stung. I’ve been stung before. I’ve felt gelatinous tendrils brush my chest, seen pink streaks well up, burn, and itch for weeks. This was different. This was a wrapping of tentacles around my legs, first one then both, then a gripping, a holding on for life, barbs penetrating my skin while I kicked, fighting against the venom entering my body to free myself of its hold and flee the warm, inviting July waters.

Once on land, my resolve faded along with my focus. I felt weak, unsteady on my feet. Family and friends circled. “What happened?” “What do you need?” But I had no idea, just pain so intense it clouded my senses. My husband ran to grab a nineteen-year-old lifeguard armed with a spray bottle of vinegar. He aimed it at my legs.

“Man, she got hit pretty bad,” I heard the Baywatch boy tell my husband. “Get her home and into the shower. She’s gonna wanna wash her legs with freshwater. After that, more vinegar. Some people”—his tan face turned bright pink and he looked down at his bare bronze feet—“say piss works best.”

I don’t remember walking the block and a half back to our condo, but I remember standing in the shower, watching water and urine run down my shaking legs and into the drain.

The welts around my ankles settled into red curving lines and tiny circles, an outline of the creature’s tentacles that didn’t fade until well into that fall. The marks fascinated me. The physical reminder of our fight felt right. It deserved to be commemorated, like the stretch marks on my belly remind me of months of pregnancy, like the gray streaks in my hair commemorate four decades of life. When the tentacle trail marks finally faded, I missed them. I even considered having them tattooed in that exact spot so I would never forget my intimate, chance encounter with a strange being from an underwater world.

The physical reminder of our fight felt right. It deserved to be commemorated, like the stretch marks on my belly remind me of months of pregnancy, like the gray streaks in my hair commemorate four decades of life.

I never forget the time my dad got lost and we ended up turning around on a narrow dirt road halfway up a mountain near Olympia, Washington. When he finally chanced a multi-point turn and I felt the rear passenger wheel beneath me slip off the cliff, spinning hopelessly over the chasm, I gripped my baby brother and held onto him as my dad popped the van into gear and gunned us forward, back to the road and safety. Years later, after watching Fight Club the day before his wedding, my then-not-so-baby brother would simulate a similar experience, pouring lye onto his bare flesh until it bubbled into a nasty weeping crater on the back of his hand. The next day, standing outside the church in his tux, hand bandaged, he grinned. “Just had to remind myself I was alive.”

Last weekend, as I walked along the beach with my husband, I was unable to shake visions of my Nana. My Nana is dying. As I drive the kids to school, teach classes and attend meetings, shop for groceries, cook dinners and pack lunches, she lies in the nursing home, no longer aware of anything, even the pain that triggers her emaciated limbs to twitch and writhe. My mother’s there now, monitoring the morphine, one last attempt to keep her comfortable. My family and I stop by to visit as we can, but we’re no longer sure she’s aware of our presence. Yesterday, when I leaned over her bed and called to her, ice blue eyes and dry mouth shot open, her head turning and skeletal hand reaching toward the sound of my voice for a moment, before the fire extinguished and she fell back into labored breathing.

Despite my appreciation of near-death moments, it feels wrong for my life to coexist with my grandmother’s dying. It feels wrong that die is a verb, that it has a present progressive form: I am dying, you are dying, she is dying, we are dying. Die is so much easier as a noun—death—or even an adjective: dead. My Nana’s death was hard, but a blessing. My father, too, is dead. The shift to noun or adjective makes the pain and suffering abstract, or places it in the past, behind us. But the verb is the reality of the moment: My grandmother is dying. While I live and love, nourish my living body, my grandmother is dying.

Looking across the sand, I noticed something ahead on the beach—a jellyfish, one of the many harmless mushroom jellies that litter the Tybee Island beach in winter—and my visions of my grandmother shift, leaving the nursing home and leading to the St. Augustine beach where I walked with her so many times over the years, looking for shells and jellyfish. My Nana would always bring a shovel.

“This one,” she’d say, scooping up the unfortunate invertebrate, “isn’t quite dead,” and she’d fling the creature back into the ocean. I tried not to look back, sure the waves would wash the poor jellyfish back onto the beach. After we’d walked a ways, talking, picking up shells, and “rescuing” more jellyfish, we’d turn around and head back. I always wondered how many of the moon and cannonball jellies on the return trip had already been “saved” once. But my nana would never give up on them.

“This one,” she’d say, scooping up the unfortunate invertebrate, “isn’t quite dead,” and she’d fling the creature back into the ocean. I tried not to look back, sure the waves would wash the poor jellyfish back onto the beach.

“I wish she’d just let go,” my mom confessed yesterday at the nursing home.

“Me, too,” I said. It was hard to see her in so much pain. Perhaps, if she still had the presence of mind she’d had twenty years ago—when she was an immigrant-turned-translator for various government and community agencies, a woman who traveled well into her eighties—she would have let go, never wanting to lose her fierce independence. But perhaps she’s still fighting, refusing to surrender to reality, to admit defeat.

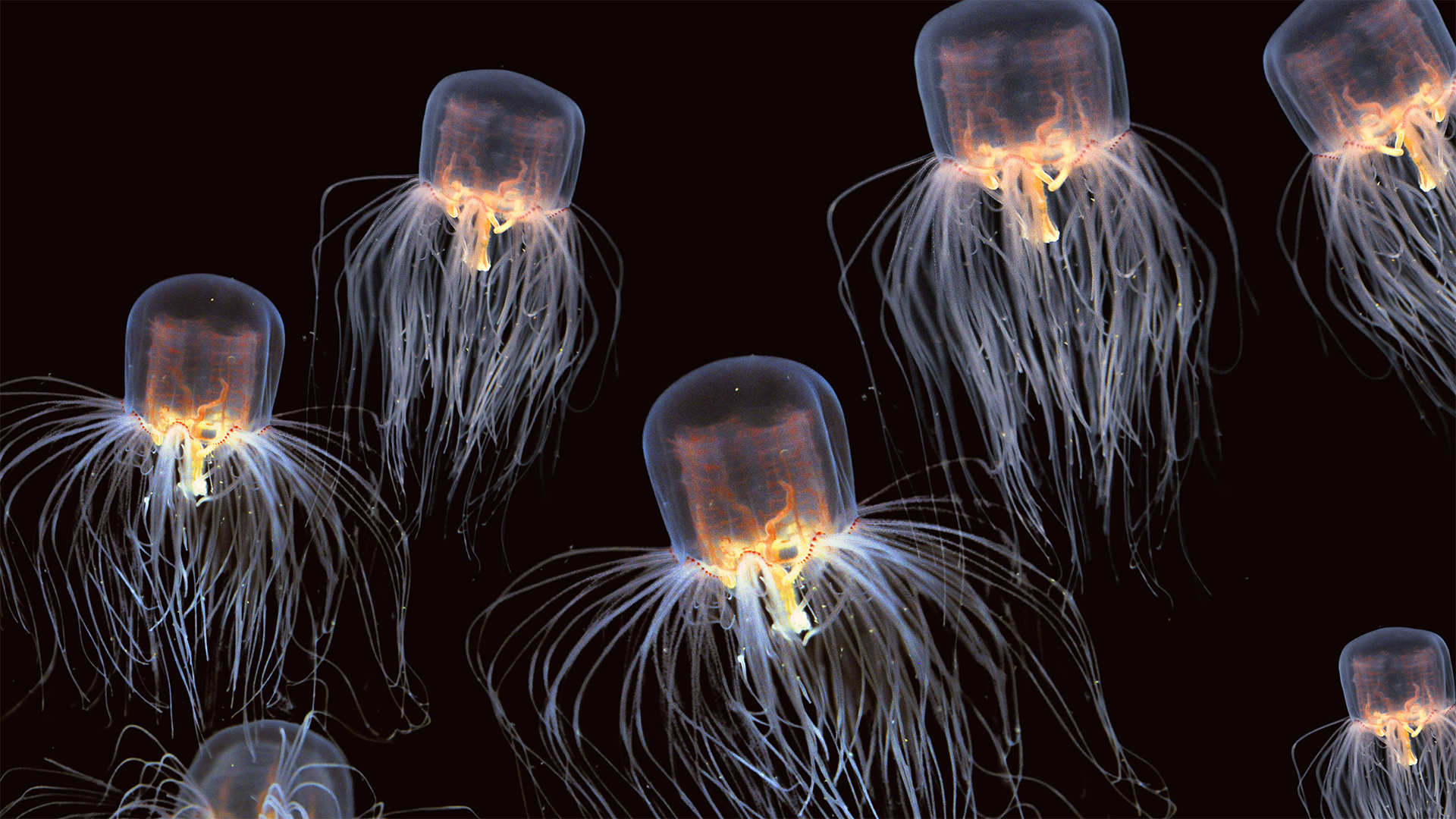

After much Googling, I stumbled upon the identity of the invisible creature whose tentacles found my legs in the cloudy Tybee waters: Chiropsalmus quadrumanus, also known as the Four-Handed Box Jellyfish. Less dangerous than its Australian cousin, the deadly chironex fleckeri (Latin for “hand of death”), this box jelly is common along the East Coast shore from North Carolina south to Florida. Unlike other jellies that drift at the whim of the sea, these box jellyfish swim, their muscular, transparent, bell-shaped bodies propelling them at speeds of up to twenty feet per minute and their complex eyes sensing light and dark in murky waters. They are not the mushroom and cannonball varieties scattered on the beach. They are underwater warriors, survivors, fighting, like my nana, until the end. Knowing, like my brother, how the fight can fill us with life.

About the author

Jessica Snow Pisano is a senior lecturer at the University of North Carolina at Asheville, where she teaches first-year writing and supervises teaching licensure students. She lives in Asheville with her husband, two children, two dogs, three cats, and a neighborhood bear she calls Peter.